“Rain Has Fallen”: Barber’s Three Songs, Op. 10

Chamber pot that probably saw a fair amount of tinkle in its day

What could classical songs have to do with the sound of urine tinkling in a chamber-pot?

The Goal of Living is to Grow, my song recital with the wonderful Victoria Kirsch, will be taking place next Thursday, February 6 2025, and next Friday, February 7 2025, in Tacoma and Seattle respectively. We are presenting a wonderful selection from the repertoire of the art song, and I’ve been moved to share my thoughts on each of the song-cycles we are presenting here in blog form. If you go back two posts in this blog, you’ll find my article on Schumann’s Liederkreis, op. 39, which explains a little general information about the genre of art-song as a whole, particularly the satisfying marriage of poetry and music in this genre.

Our listeners will have an opportunity to very directly appreciate this marriage with our two English-language cycles, Samuel Barber’s Three Songs, op. 10, and Mark Carlson’s This Is the Garden.

(Oh by the way, what’s the deal with this notation “op.”? It’s short for “opus,” Latin for “work'“ [also the hopelessly naïve and optimistic penguin from Bloom County], and is simply a publication number, identifying any given work by its order in the composer’s catalog).

With English lyrics, there is no need for the intermediary of the translations-sheet for the [English-speaking] listener to perceive the relationship between words and music. Carlson’s and Barber’s cycles also have the great virtue of setting the work of poets of the highest caliber: e.e. cummings in the case of This is the Garden, and James Joyce in the case of the Three Songs, op. 10.

Both poets are master wordsmiths, but both are also unapologetic modernists. For the everyday reader, their names may even be a little intimidating! —You might expect thorny and incomprehensible word salad from these masters of the abstract & the stream of consciousness.

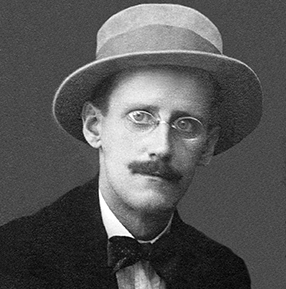

James Joyce before the eye-patch. Ain’t he a freaky-looking little weirdo?

In the case of Barber’s three settings of Joyce poems, this fear is utterly unfounded. Barber here sets three poems from an early-period Joyce, before he had yet achieved the more difficult style of his later works. The poems are lyrical, formally straightforward, and quite poignant. The poetry comes from a 1907 collection of Joyce’s poetry called Chamber Music. Though published in 1907, remarks of Joyce’s indicate that a lot of the poems were written significantly earlier. The poet Ezra Pound praised these early poems for their “delicate temperament”—a quality not-so-often ascribed to Joyce’s works.

All thirty-six of the poems in Chamber Music are love poems. Joyce has indicated they were love poems to an imagined beloved, a woman he conjured before he eventually met Nora Barnacle, famously the love of his life. Those familiar with the saga of Joyce & Barnacle know that their love was intense, earthy, and carnal in the extreme. If you’ve never read their extremely bawdy love-letters I can only recommend them in the most glowing terms (though they’re not for the weak-of-stomach). His casual bawdiness and refusal to deny the physical body are absolutely one of the most endearing things about Joyce’s persona and work… I mention this not because the poems in our Opus 10 songs are at all bawdy (in fact, they are anything but), but by way of circling back to the question I posed about the chamber-pot at the beginning of this essay.

In researching about these poems, I was delighted to learn that Joyce would later claim that the title “Chamber Music” for the entire collection was a reference to the “music” of urine tinkling in a chamber pot. How hilarious, and how in keeping with all that we know of Joyce!

In fact, the chamber-pot pun is almost certainly not the original reason for the title, but a later embellishment via Joyce’s typically naughty sense of humor. The title Chamber Music almost certainly refers to the song-like quality of the poems, a conclusion borne out by the frequency with which poems from this collection have had musical settings, both by classical composers and musicians in other genres. Nevertheless, there does seem to be a specific incident connected to the chamber-pot legend:

[T]he chamber-pot connotation has its origin in a visit [Joyce] made, accompanied by Oliver Gogarty, to a young widow named Jenny in May 1904. The three of them drank porter while Joyce read manuscript versions of the poems aloud - and, at one point, Jenny retreated behind a screen to make use of a chamber pot. Gogarty commented, "There's a critic for you!". When Joyce later told this story to Stanislaus, his brother agreed that it was a "favourable omen".

(And may the good lord forgive me for quoting Wikipedia, though the Wikipedia page attributes this anecdote to “Richard Ellman, from a 1949 conversation with Eva Joyce, the author's sister,” as reported in Ellmann, Richard. James Joyce, Oxford University Press, 1959, revised edition 1983.)

It can only be quite humorous then, (at least if you are as immature as I am), that the very first sound we hear in our Barber set are delicate raindrops: the first song in the set is on the poem “Rain is Falling,” and Barber begins with the piano painting the drip-drops of an all-day drizzle. I have no idea whether Barber knew about Joyce’s joke about the title of his collection; I fully expect that this beginning is NOT any sort of in-joke, though I reserve my right to be quietly amused by it.

Considering the song a bit more seriously, we can only be moved to reverie by the beautiful tone-painting; the piano’s delicate drizzle goes through many permutations, at times sounding like trickles off a rooftop, at others like a raging monsoon. At all points, the intensity of the rainshower is always a mirror of the poet/singer’s emotional state: his walk down the way of memory eventually instigates a burning need to “speak to [the] heart” of his beloved.

Rain has fallen all the day.

O come among the laden trees:

The leaves lie thick upon the way

Of memories.

Staying a little by the way

Of memories shall we depart.

Come, my beloved, where I may

Speak to your heart.

The second song, too, traces a journey from a melancholic calm, to a more stabbing intensity, as Barber highlights the angst of the winter crying “sleep no more”:

Sleep now, O sleep now,

O you unquiet heart!

A voice crying "Sleep now"

Is heard in my heart.

The voice of the winter

Is heard at the door.

O sleep, for the winter

Is crying "Sleep no more."

My kiss will give peace now

And quiet to your heart -- -

Sleep on in peace now,

O you unquiet heart!

The third song is all rush and thunder, as we hear of the trampling army that the poet/singer perceives approaching… as in the former songs, though, the image of the army is really a metaphor for some experience of the poet/singer’s love-wracked interior:

I hear an army charging upon the land,

And the thunder of horses plunging, foam about their knees:

Arrogant, in black armour, behind them stand,

Disdaining the reins, with fluttering whips, the charioteers.

They cry unto the night their battle-name:

I moan in sleep when I hear afar their whirling laughter.

They cleave the gloom of dreams, a blinding flame,

Clanging, clanging upon the heart as upon an anvil.

They come shaking in triumph their long, green hair:

They come out of the sea and run shouting by the shore.

My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair?

My love, my love, my love, why have you left me alone?

…in fact, it seems the army is rushing into the poet/singer’s dreams directly out of the blackness of deep sleep. Barber’s setting does beautiful justice to this poem, a poem that no less a critic than W.B. Yeats called “a technical and emotional masterpiece.”

Come hear this masterpiece set by Barber on February 6th and 7th—both venues have adequate bathrooms and chamber pots should not be needed.