Finding the Fine in the Folk: Ravel’s “5 Greek Popular Songs”

In my last blog post, about Robert Schumann’s Liederkreis, Op. 39, I mentioned the inimitable Bob Dylan—I have recently seen the biopic A Complete Unknown. I was relating Bob’s work to the genre of the art song overall, both of which can be described as “poetry set to music.” As I sit down to write a little meditation of Ravel’s 5 Popular Greek Melodies, I once again have No Direction Home in mind.

I’m thinking of that wonderful phenomenon called FOLK MUSIC. In No Direction Home, we are plunged into the U.S. folk scene of the early- to mid-sixties. Here we meet towering figures like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie—musicians who believed not only in the authenticity of their folk singing, but also in its capacity for social influence.

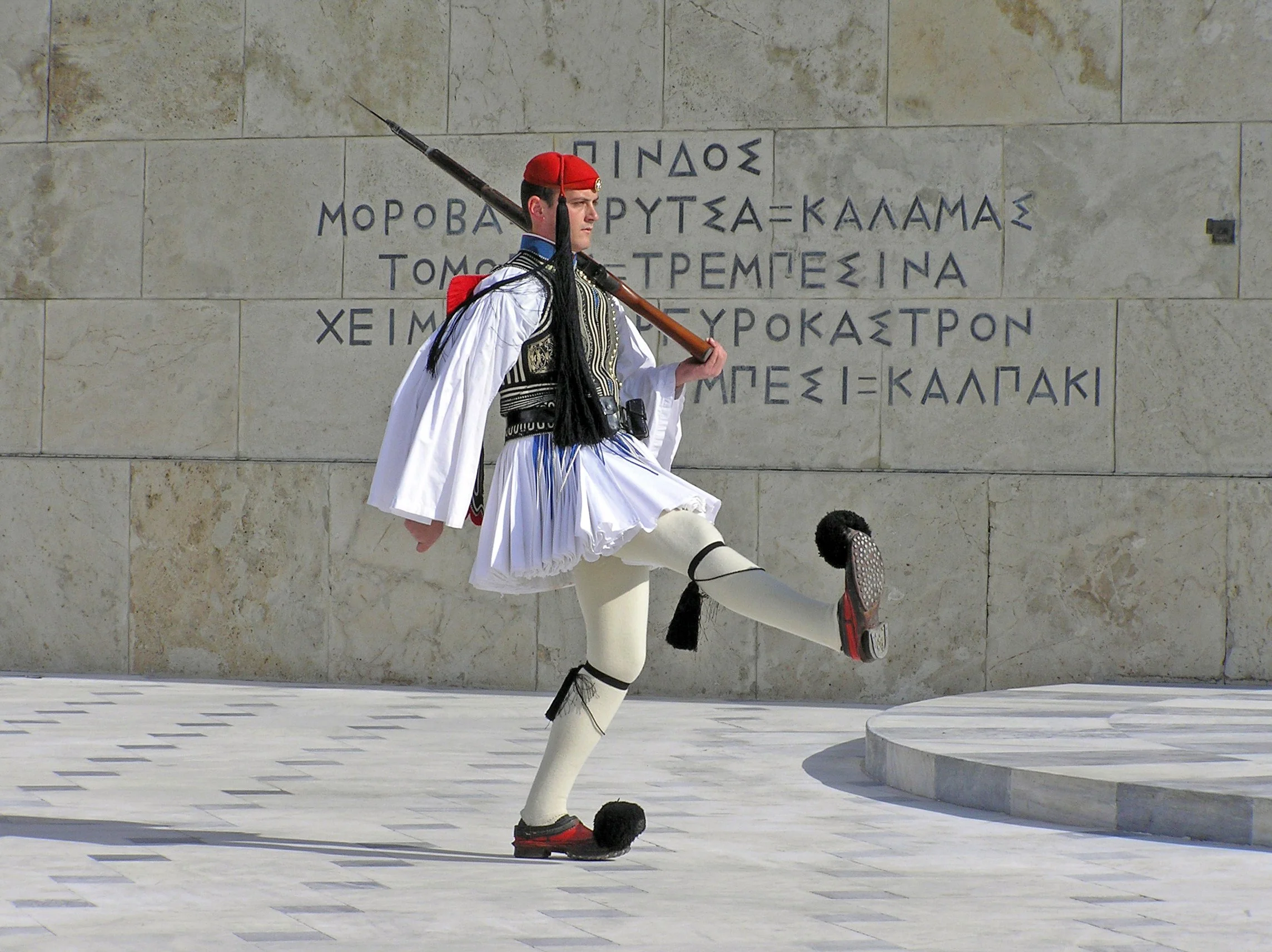

I find folk music so wonderful and interesting…what sort of music arises spontaneously from populations who are neither conservatory-trained nor paid for their musical efforts? It is a favorite fact of mine that every single human culture produces music—one could argue, even, that music is somehow a biological trait of the human animal! I’ve always delighted in folk music of various cultures because to me it speaks very poignantly of nothing less than what it means to be human. Of course, a culture’s folk music will end up reflecting the important aspects of everyday life for them…agricultural societies will have field songs, warrior cultures will have battle hymns, and so on and so on.

The genre of music called “Folk” in your local record store, of course, does not compass all the world’s folk music traditions…but of course it is the record store’s British-American folk that we’re made to think of in A Complete Unknown, and in another great movie I rewatched recently, the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis. Still, the premise remains: this is the music that comes from the people, from the workers, the villagers, the homemakers, rather than from the conservatory-trained elites.

There is a wonderful scene depicting an encounter between the two types of musician in Inside Llewyn Davis; Davis, a folksinger, attends a dinner party with his friends who are on faculty at Columbia, and is introduced to a couple musicians from “Musica Anticha,” a Baroque group. Trying to relate, Davis asks if they know his childhood piano teacher, Mrs. Siegelstein. A bit flummoxed by the question, the Baroque keyboardist can only cordially ask, “uh, does she play early music?”

In our recital, the encounter of the folk with the refined is much more fertile, and less awkward. The Greek songs that Ravel orchestrates as his 5 mélodies populaires grècques (5 Popular Greek Melodies, or more idiomatically translated, 5 Greek Folk Songs) are earthy, full of life, and yet at times quite exquisitely delicate, and even unexpectedly complex. The first song, “The Awakening of the Bride,” is jocular and excited, the second, “Yonder by the church,” is solemn and mournful. The third, “What gallant is my equal?,” is masculine and braggadocious, while the fourth, “Song of the mastic-harvesters,” is pensive, lyrical, and meandering. The cycle is capped by “All merry!,” a rambunctious dance with plenty of rhythmic “laralarala’s.”

This cycle cannot even properly be said to be “by” Ravel, though popular usage names him the composer. In reality, he is the arranger, or even more accurately, the orchestrator, of melodic materials he did not invent. This cycle is a marriage of the folk and the conservatory—Ravel’s accompaniments are slick, urbane, and musically modern. Yet they also elevate and highlight the inherent characters of the folk melodies; they neither erase nor overshadow the beauty and vitality of the respective folk songs. This meeting of the folk and the “classical” is much more productive than the one Llewyn Davis experiences in that uptown apartment.

Singing these songs in Greek greatly enhances the feeling of authenticity for me. These five songs were set by Ravel in French translation. Sung in French, they sound hopelessly urbane, thanks to French’s languorous nasals and endless vowel sounds. The Greek lyrics have been a delight for me to study…Greek has sonorous consonants separated by pure vowels, like the vowels of Italian or Spanish. It sounds both stately and earthy, both high and low, both ancient and timeless. I truly believe everyone will enjoy hearing these songs in the original Greek!

In the overall flow of this recital, I can only appreciate the note of folkish vitality that these songs introduce, a counterbalance to the weighty German Romanticism of Eichendorff, and to the cerebral English Modernism of Joyce and cummings. Come and hear!